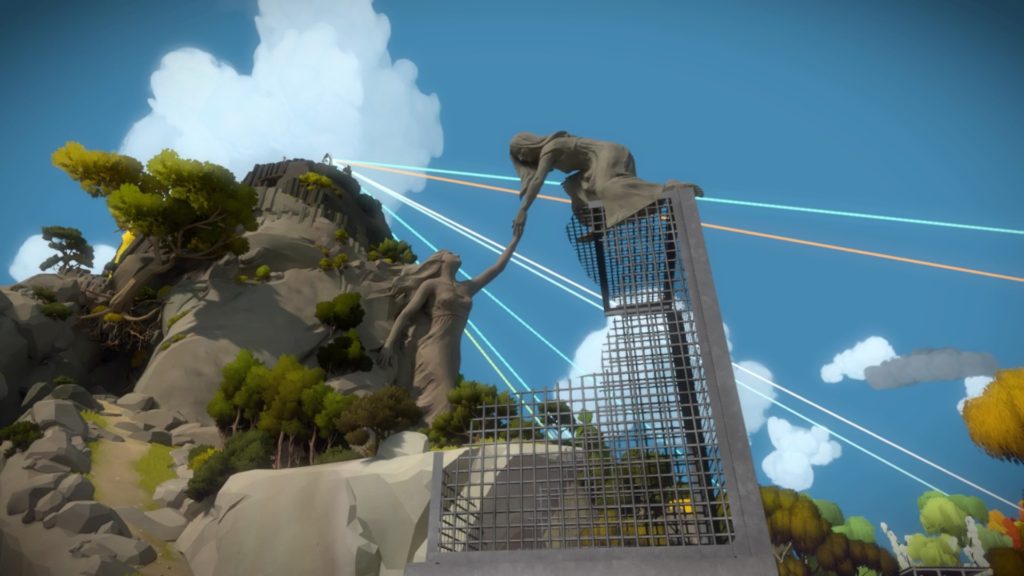

From the moment you start playing The Witness (2016), you are on your own. The game wakes you up in a dark tunnel and teaches you how to move. At the end of that tunnel you encounter the first of more than 500 line-drawing puzzles that make up the core of the game, and you learn how to solve it. Once you solve it, and the ones that follow, you have learned the basic gameplay mechanics and gained full access to the lush, deserted island that is now yours to explore. The questions mount: What am I doing here? Who put all these labyrinthine puzzles all across this island? And why are the only other people on the island made of stone?

There might be answers to these questions, but I soon stopped looking for them. The Witness challenges the whole idea of narrative in a game, making the absence of a clear backstory one of the core intrigues that keeps you playing. You are surrounded by suggestions that something happened here, but what it is ain’t exactly clear. All you can do is make your way through the musicless, motionless world (where even the clouds sit still as if painted on the sky), unlocking the island’s secrets one puzzle at a time.

Because ultimately, the thrill of solving these puzzles one-by-one drives you forward more than anything else. I can’t remember the last game I played in which I was so thoroughly stumped by so many of its obstacles, and then felt so proud at my ability to eventually figure them out. We’re talking hours and hours of staring at these panels, listening to that sonar ping and drawing one failed shape after another until the answer clicked into place. (As ambient noise for my living room for entire evenings at a time, my wife couldn’t get enough, as you can imagine.)

In the meantime, as you explore every beautiful nook and cranny of the island, you stumble upon dozens of audio clips of quotes from famous historical figures, from Einstein to Augustine of Hippo, that have just been scattered about the landscape. Each one manages to sound vaguely profound while illuminating nothing about your character or the world you’ve inhabited. The same could be said of the enigmatic video logs that you can unlock, through solving particularly challenging puzzles. The one embedded below, a talk by Rupert Spira about nonduality (of course!), runs for over thirty minutes. Access to these videos becomes the only collectible of sorts in a game where otherwise the only inventory is your growing knowledge of how the puzzles work, but they also yield a whole new host of questions. If you have the patience to watch them, what meaning do you come away with regarding the plot of The Witness?

Perhaps these features are more pretentious than anything else, and I’ll admit that after banging my head against a wall to solve a challenging puzzle only to earn the privilege of watching static-camera footage of a philosophy lecture, I felt some frustration about the lack of answers here.

But in those moments, I was missing the point. The puzzles, and the way they make you think, are the answer. Like the most lavish places of worship are meant to elevate the consciousness to something above its “default mode” so that prayer seems the reasonable response, the enigmatic, humanities potpourri that creator Jonathan Blow scattered around his island are, I suspect, intended to prime your mind for the analysis necessary to solve puzzles that often require you to think quite literally “outside-the-box.” Everything around you might be a component to a puzzle – the sound of your character’s footsteps, the shadow you cast on the ground, the shape of a river, the pattern of birds chirping in the background. The game trains you to look at the world in ways that sharpen your powers of observation and problem-solving.

All these elements of The Witness speak to its most postmodern impulses – it is trying to heighten your state of mind and complicate your understanding of what it means to play a game, not to simply transfer a story to you or act as a fun distraction. A story might blur its way into your mind as you enter new buildings, activate new machines, and find new stone people because of the puzzles you’ve solved, but it will inevitably be half-covered in shadow, much like the workings of the mind that got you there.

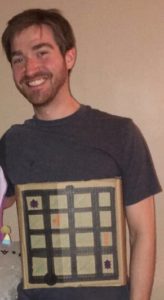

In closing, I enjoyed The Witness so much that I dressed up as one of its puzzles for Halloween this year.